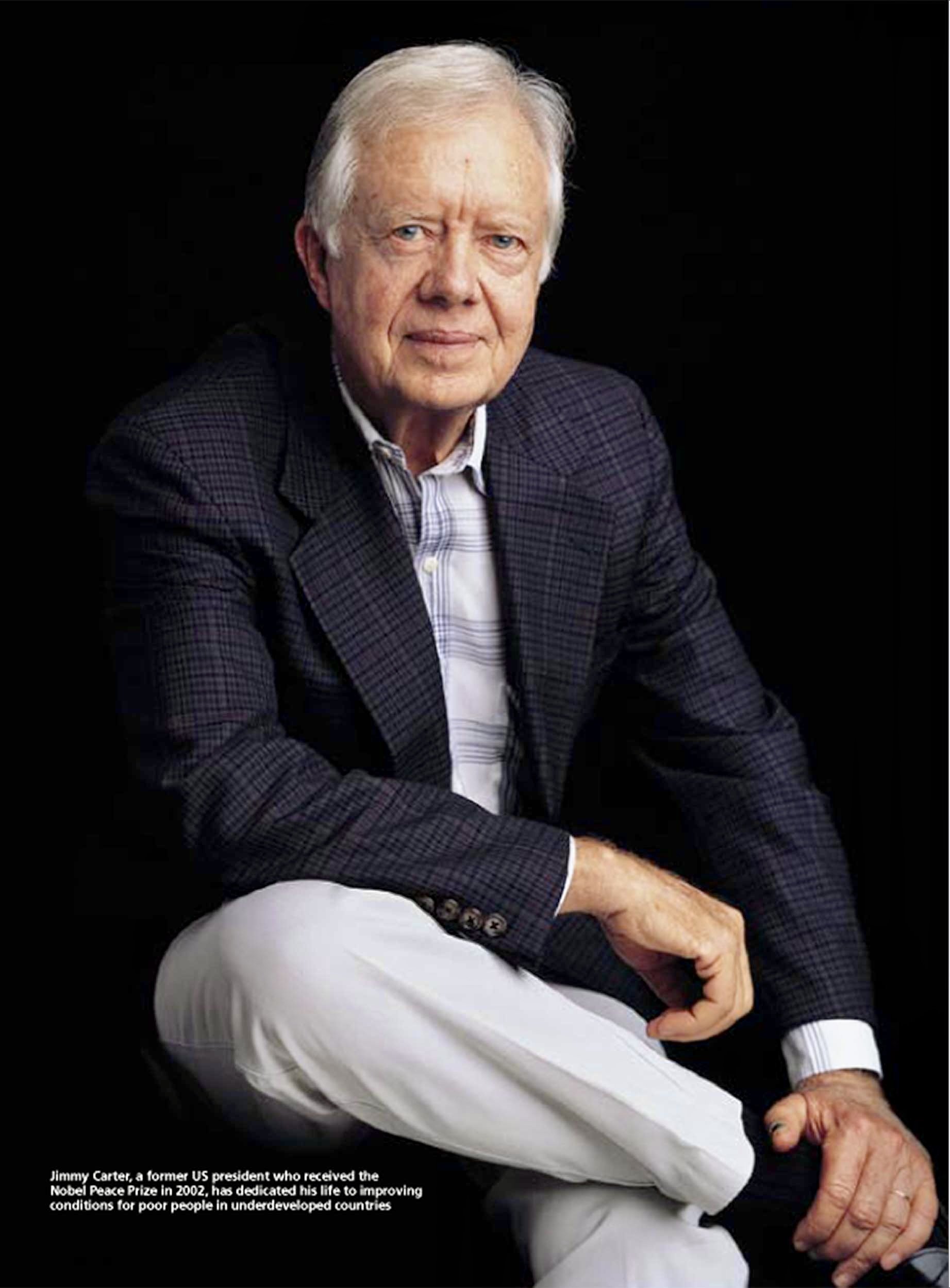

Interviewing President Jimmy Carter

/In the spring of 2005, one of the world’s largest investment banks/financial services firms asked me how they could increase engagement with their quarterly magazine for the firm’s 45,000 richest U.S. clients.

We developed a number of recommendations, all intended to make the magazine’s stories, features, and photos more competitive with other must-read publications these clients subscribed to—not just the WSJ, NYTimes, Wired, and Vanity Fair but consumer catalogs from companies like Patagonia and Williams Sonoma.

Most of our ideas were nixed by their legal/compliance department. But one suggestion—an interview series with celebrities on wealth topics—aligned with the firm’s interest in showcasing its philanthropic advisory group. Could we get an interview with President Jimmy Carter on his work for Habitat for Humanity?

Sure. To me, the deal was pretty straightforward: the firm gets an attention-grabbing interview, and Carter gets his non-profit in front of many thousand potential donors.

It worked. With two phone calls, I’d secured a half hour with the President. “Not a minute more—he’s a Navy man and he’s very conscious of the time.” And no questions about Habitat for Humanity. He would only talk about The Carter Center.

He picked up the line directly, as I recall, in that familiar voice with the slightly lockjaw manner of speech common to the coastal South. Compared to most Southerners, he spoke surprisingly quickly. Certainly the sharpest 80-year-old I’d ever talked with. His well-worn line that he’d been “involuntarily retired from the White House” struck me as odd and a bit tone-deaf; wasn’t he defeated in a democratic election? His voice was as steely and determined as his gaze is said to have been.

What occurred to me yesterday as I retyped this interview is the strong Protestant evangelical current in Carter’s post-presidential work. He had an almost missionary insistence on making people’s lives better. On our call he was all business; in retirement, he was resolved to make most of his waking moments count for something.

The interview was a success, by my lights—we ended up talking for over 45 minutes, over 50% more than what I was strictly promised. Maybe he enjoyed it as well.

Going from the world’s most powerful person to a private citizen with no particular agenda—that must have been unimaginably difficult.

When I was involuntarily retired from the White House I was surprised, taken aback, and discouraged. I had no opportunity for gainful employment. I realized that I had a life expectancy of 25 years. Remember, I was one of the youngest survivors of the White House [he was 56 on Reagan’s 1981 inauguration].

How did you decide to devote your new life to humanitarianism?

I assessed my talents, abilities, and interests. I was most proud of the peace agreement I had mediated between Egypt and Israel—by the way, not a word of which has been violated in 26 years.

What if I could emulate that on a smaller scale? Helping everyone from individuals to countries settle their disputes? It was something tangible I could do. That was the concept for The Carter Center.

Most philanthropists have an “aha” moment when they discover a connection between themselves and the wider world. Was this yours?

As Rosalynn wrote in our book Everything to Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life (Random House, 1987), the idea for The Carter Center came to me in the middle of the night.

But the connection was there all my life. My mother was a registered nurse; she took care of all our neighbors, none of whom were white. So I was brought up seeing first-hand the ravages of racial discrimination and the deprivation of the poorest of people. It has influenced my life, but especially since the presidency.

You were a successful politician, rising from the Georgia state senate to the U.S. presidency in 16 years. How do the satisfactions of governing compare to your current work?

As president, you’re focused on very large issues—a nuclear agreement with the USSR, diplomatic relations with China, the situation in the Middle East, the domestic budget. There are few opportunities to understand the plight of the most destitute.

The impact I have on people’s lives now is much more immediate. I see them develop a sense of self-respect, hope, and confidence in themselves for the first time in their lives. They’ve known no example of this—they’ve just gotten lots of promises from distant countries.

You’re an extraordinarily hands-on person. Does involvement drive enthusiasm?

Absolutely. The things we do through The Carter Center are so intimately personal. We put medicine in people’s mouths. We show them that their water is full of parasites, and how to deal with that. We teach them to wash their faces and to use a latrine, to avoid trachoma. We teach them to grow corn, rice, millet, wheat, soybeans. It’s very gratifying.

Involvement cements our donors’ ties to us. They become almost obsessed with benevolent causes. It’s no longer a theoretical concept.

You do a lot of traveling.

Actually going to the place is important. Rosalynn and I have visited more than 120 nations since leaving the White House.

International travel is exciting and challenging. It can also be enlightening. I advise people who travel to get out of the international hotels and go to the villages. Talk to shopkeepers. Wander through neighborhoods. Too many American travelers don’t do this, and their experience is almost like visiting the suburbs of New York City.

The number-one reason most affluent people don’t give is the fear of doing harm. As the leader of a humanitarian institution and an active participant, how do you ensure your work actually ends up helping people?

That’s a concern. We work side-by-side with many organizations. Some establish a nice office in the nation’s capital, install phones, buy pick-up trucks, hire a staff. Then they start meeting with the assistant minister of health.

There are a few things to look for in an organization such as ours. First, what are they actually doing? Too many groups just visit, bring in experts, have conferences, and publish nice-looking documents. These things have their place, but the goal is to achieve something tangible, whether it’s alleviating suffering or bringing about peace.

Second, do they have a clear plan? We start by meeting with a country’s ruler and his entire cabinet. I set expectations—we’ll send the foremost experts in the world, you’ll pay for your own people. If we buy a bicycle for you, you’ll pay us back. We’ll be here five years, at which time we want you to be self-sufficient. Then we sign a contract between The Carter Center and Bali, Burkina Faso—whatever country it is we’re working with.

We try to undertake only programs with tangible, quantifiable outcomes. We’re the hands-on people. It’s one of the things that has made our projects attractive to donors.

We also measure results. We can quantify our accomplishments in almost everything we do. We know exactly how many latrines we’ve built in Ethiopia in our effort to wipe out trachoma. We know how many cases of Guinea worm are out there, and which villages they’re in, so we can better focus on eradication.

Look for accountability. For our 2,500 donors who give $1,000 a year, we bring them here for one full day once a year to tell them how we’re spending their money.

We also stay effective by avoiding duplication. It’s one of our tenets. If the World Bank, the World Health Organization, or Harvard University is already doing something adequate, we don’t get involved. We’re there to fill vacuums.

In other words, don’t go where everyone else is.

Everyone wants to go to Kenya—it has great parks, Nairobi is a wonderful city.

Here’s a cautionary tale: I once visited Kenyan president Danial Arap Moy. His minister of health had just told him there were 200 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Nairobi alone—and he didn’t have time to meet with all of them, much less work with them!

Today’s generation of philanthropists puts a premium on education. They want to know all about what they’re giving to before they invest their time and money. How important is this?

Very. We offer this opportunity to our donors—an invitation to go with us to Zambia, to Mali, and help us monitor an election, for instance. It does a few things. First, we get their help. Second, we get transportation (some of them have jets). Third, we get them immersed in the culture, the history, the politics. This January it was Israel’s West Bank; in December it was Mozambique. Last July it was Indonesia.

More philanthropy is actually driven by wanting to remove the heavy burden of wealth from the next generations—to help instill the right values. How have you done this with your children?

Our family has no accumulated wealth, so we don’t have that issue. But they are deeply involved in The Carter Center—when their help is needed. After all, this can’t be a Carter family expedition.

It’s been completely voluntary on their part, but they await their turn with great impatience. For instance, my middle son [Chip] hadn’t been to Israel until very recently. My youngest son, Jeff—an absolute expert on Indonesia—has worked as an election observer. And my oldest grandson [Jason], who was an intern at The Carter Center, then with the Peace Corps for 2½ years in South Africa, is now back with us. In the first election among the Palestinians this past January, he was in charge of Gaza and my daughter, Amy, was in charge of Bethlehem, with about 40 other volunteers.

At last count there were more than 66,000 grantmaking foundations in the U.S. What would you say to those who are baffled by the choices out there?

The opportunities are enormous. But many organizations are eager to help you learn about what they do.

For example, The Carter Center hosts a four-day ski weekend in the Rockies. Attendees pay their way and get acquainted with our programs. Half of the 290 people who came to our last one, in Utah, hadn’t been there, and half didn’t ski. They were there for the experience.

We also give prospective donors a chance to join us, either overseas or at The Carter Center, to learn what we’re about.

There are a lot of darn good organizations who do outstanding work. I’m proud to say that The Carter Center is just one of those organizations.

What has been the most gratifying part of your life?

When I was 70—a long time ago—Barbara Walters asked me the same question. My answer was “now.” That’s still my answer.